Thank you to Georgia Tech for providing this summary of new research by Dr. Marilyn Brown and Valentina Sanmiguel Herrera on the possibilities of combined heat and power systems as a climate solution in Georgia. Read more about the research methodology and findings here.

Buildings require enormous amounts of energy to power, heat, and cool them. When that energy comes from fossil fuels, the result is a tremendous amount of carbon emissions--in 2017, Georgia’s commercial and residential buildings were responsible for about 30% of the state’s emissions.

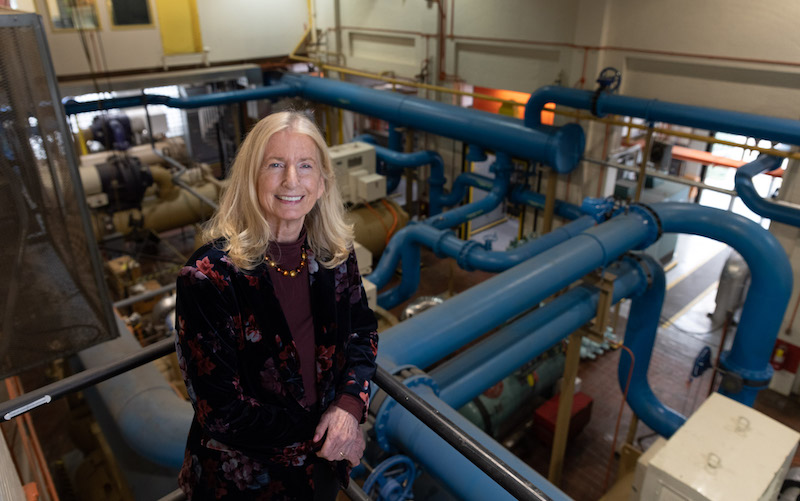

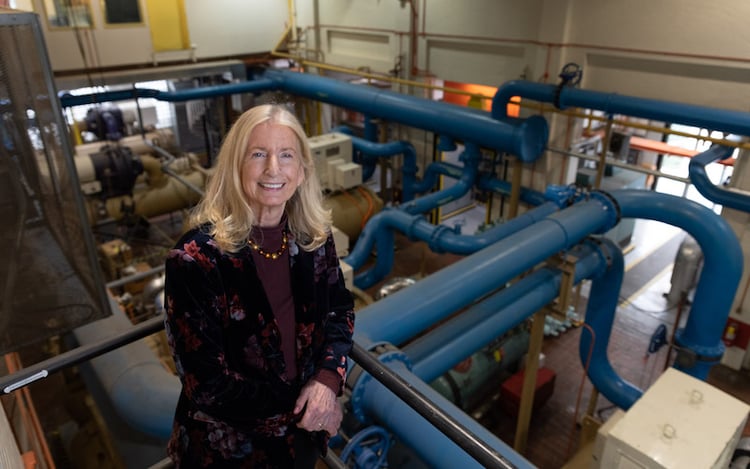

The study’s principal investigator, Marilyn Brown, at the district heating and cooling plant in the heart of Georgia Tech’s campus. While Georgia Tech is not yet operating a CHP system, it is currently examining options for lessening the campus’s energy footprint. Photo by Robert Felt, Georgia Tech.

The study’s principal investigator, Marilyn Brown, at the district heating and cooling plant in the heart of Georgia Tech’s campus. While Georgia Tech is not yet operating a CHP system, it is currently examining options for lessening the campus’s energy footprint. Photo by Robert Felt, Georgia Tech.

Reducing Emissions with Cogeneration

One effective means of reducing emissions created by commercial buildings is by leveraging cogeneration, or combined heat and power (CHP) systems. CHP co-produces electricity useful for heat and cooling, resulting in ultra-high system efficiencies, cleaner air, and more affordable energy. Georgia industries that can profit from CHP include chemical, textile, pulp and paper, and food production. Large commercial buildings, campuses, and military bases also could benefit from using co-generation as a strategy. By utilizing both electricity and heat from a single source onsite, an energy system is more reliable, resilient, and efficient - everything we want in a climate solution.

Efficiencies are found when CHP reduces peak demand on a region’s utility-operated power grid. Additionally, if there is an outage or disruption in a community’s power grid, companies with their own onsite electricity sources can reliably continue to have power.

According to new research from Georgia Tech’s School of Public Policy, Georgia could dramatically reduce our greenhouse gas emissions, create new jobs, and improve public health if more of our energy-intensive industries and commercial buildings were to utilize CHP.

Combined Heat and Power Systems Go Beyond Carbon to Benefit the Environment, the Economy, and Public Health

The Georgia Tech researchers found that 9,374 sites in our state are suitable for cogeneration. If CHP systems were added to all of them, it could reduce overall carbon emissions in Georgia by 13%. Bringing CHP to just 34 of Georgia’s industrial plants, each with 25 megawatts of electricity capacity, could reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 2%. The study authors also note that this “achievable” level of CHP adoption could add 2,000 jobs to the state; full deployment could support 13,000 new jobs.

Using data analytics, the researchers were also able to predict the economic and health benefits of CHP for Georgians. Plants converting to cogeneration could boost the state’s clean energy workforce by 2,000 to 13,000 depending on how widely the systems are adopted. Currently, the state has about 2,600 jobs in electric vehicle manufacturing and fewer than 5,000 in the solar industry, according to the 11th Annual National Solar Jobs Census 2020.

The Public Health Benefits of Cogeneration Adoption

In addition to job growth, CHP adoption could lead to dramatic health benefits for the state’s more vulnerable residents by enabling companies to generate power from their own waste heat, which would help to displace more polluting sources of electricity.

The study estimates a savings of nearly $150 million in reduced health costs and ecological damages in 2030 in the “achievable” scenario for CHP, with nearly $1 billion in health and ecological benefits if every Georgia plant identified in the study adopted CHP.

The Georgia Tech research shows the potential of CHP systems to reduce Georgia’s carbon footprint. ReEnergy’s Albany Green Energy biomass plant (pictured above) is a compelling example of CHP systems at work in Georgia. The facility, located at P&G’s paper manufacturing facility in Albany, Georgia, provides 100% of the steam energy used in the manufacturing of Bounty® paper towels and Charmin® toilet paper. It also generates electricity for Georgia Power and powers an 8.5-megawatt steam electricity generator for the nearby Marine Corps Logistics Base. The plant “serves as a testament to Albany’s viability as an ideal site for innovation and green initiatives,” said Jana Dyke, president & CEO of the Albany-Dougherty Economic Development Commission. Photo by Albany Green Energy.

The Georgia Tech research shows the potential of CHP systems to reduce Georgia’s carbon footprint. ReEnergy’s Albany Green Energy biomass plant (pictured above) is a compelling example of CHP systems at work in Georgia. The facility, located at P&G’s paper manufacturing facility in Albany, Georgia, provides 100% of the steam energy used in the manufacturing of Bounty® paper towels and Charmin® toilet paper. It also generates electricity for Georgia Power and powers an 8.5-megawatt steam electricity generator for the nearby Marine Corps Logistics Base. The plant “serves as a testament to Albany’s viability as an ideal site for innovation and green initiatives,” said Jana Dyke, president & CEO of the Albany-Dougherty Economic Development Commission. Photo by Albany Green Energy.

Examining the Barriers to Widespread Adoption of Cogeneration

Despite the advantages of CHP, there remain hurdles to its adoption, one of the most important of which is the costs involved. Establishing these facilities is capital-intensive, ranging from tens of millions for a campus CHP plant to hundreds of millions for a large plant at an industrial site. Once built, these facilities require their own workforce to operate.

Another hurdle is the relatively low cost of electricity in the Southeast, which means it will take longer to achieve a reasonable payback on those systems. Georgia’s industries that wish to be competitive globally would be wise to look at CHP; however, considering that the rest of the world is embracing renewable and recycled energy at a faster rate than the U.S., the researchers note.

In the paper, the research team cites three ways to improve the business case for CHP: clean energy portfolio standards, regulatory reform, and financial incentives such as tax credits.

Their findings also hold up North Carolina as a useful case study to demonstrate the effectiveness of these methods. The state already has policies in place that incentivize the use of renewable energy and CHP systems. North Carolina has also embraced converting waste from swine and poultry-feeding operations into renewable energy. In addition, North Carolina State University recently installed its second CHP facility on campus.

Cogeneration Systems at Georgia Tech

While Georgia Tech is not yet operating a CHP system, the Campus Sustainability Committee is currently examining options for reducing their energy footprint. “Georgia Tech seeks to leverage Dr. Brown’s important research, and the deep faculty expertise at Georgia Tech in climate solutions, as we advance the development of a campus-wide Carbon Neutrality Plan and Campus Master Plan in 2022,” said Anne Rogers, associate director, Office of Campus Sustainability. “The Campus Master and Carbon Neutrality Plan will provide a roadmap to implementing sustainable infrastructure solutions to advance Georgia Tech’s strategic goals.”

Drawdown Georgia’s research team leader Dr. Marilyn Brown emphasizes that Georgia utilities should get behind cogeneration projects to help the state reduce its carbon footprint. “In industries where CHP is well understood, and there are solidly established businesses, it’s a great investment and a smart way to keep jobs in the community, while being good for the environment. The hurdles are not about technology; they are all about policies and business models,” she concluded.

Learn more about CHP as a Drawdown Georgia climate solution here; you may also access the new research, “Combined Heat and Power as a Platform for Clean Energy Systems,” in the Applied Energy journal.